USNWR should considering incorporating conditional scholarship statistics into its new methodology

Earlier, I blogged about how USNWR should considering incorporating academic attrition into its methodology. Another publicly-available piece of data that would redound to the benefit of students would be conditional scholarship statistics.

Law students offer significant “merit based” aid—that is, based mostly on LSAT and UGPA figures of incoming students. The higher the stats, the higher the award in an effort to attract the highest caliber students to an institution. They also offer significant awards to students who are above the targeted medians of an incoming class, which feeds back into the USNWR rankings.

Law schools will sometimes “condition” those merit-based awards on law school performance, a “stipulation” in order to retain the scholarship in the second and third years of law school. The failure to meet the “stipulation” means the loss or reduction of one’s scholarship—and it means the student must pay the sticker price for the second and third years of law school, or at least a higher price than the students had anticipated based on the original award.

The most basic (and understandable) condition is that a student must remain in “academic good standing,” which at most schools is a pretty low GPA closely tied to academic dismissal (and at most schools, academic dismissal rates are at or near zero).

But the ABA disclosure is something different: “A conditional scholarship is any financial aid award, the retention of which is dependent upon the student maintaining a minimum grade point average or class standing, other than that ordinarily required to remain in good academic standing.”

About two-thirds of law schools in the most recent ABA disclosures report that they had zero reduced or eliminated scholarships for the 2019-2020 school year. 64 schools reported some number of reduced or eliminated scholarships, and the figures are often quite high. If a school gives many awards but requires students to be in the top half or top third of the class, it can be quite challenging for all awardees to maintain their place. One bad grade or rough day during exams in a point of huge compression of GPAs in a law school class can mean literally tens of thousands of dollars in new debt.

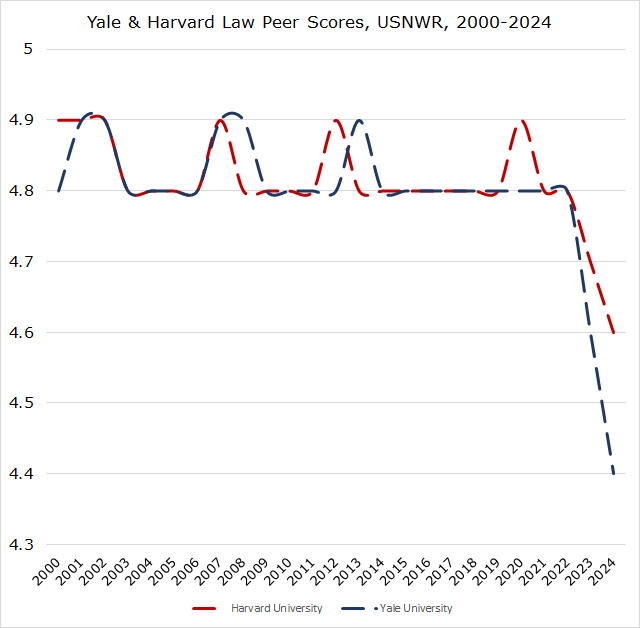

Below is a chart of the reported data from schools about their conditional scholarship and where they fall. The chart is sorted by USNWR “peer score.” (Recall all the dots at the bottom are the 133 schools that reported zero reduced or eliminated scholarships.)

These percentages are the percentage of all students, not just of scholarship recipients—it’s meant to reflect the percentage among the incoming student body as a whole (even those without scholarships) to offer some better comparisons across schools. (Limiting the data to only students who received scholarships would make these percentages higher.)

It would be a useful point of information for prospective law students to know the likelihood that their scholarship award will be reduced or eliminated. (That said, prospective students likely have biases that make them believe they will “beat the odds” and not be one of the students who faces a reduced or eliminated scholarship.)

A justification for conditional scholarships goes something like this: “We are recruiting you because we believe you will be an outstanding member of the class, and this merit award is in anticipation of your outstanding performance. If you are unable to achieve that performance, then we will reduce the award.”

I’m not sure that’s really what merit-based awards are about. They are principally about capturing high-end students, yes, for their incoming metrics (including LSAT and UGPA). It is not, essentially, a “bet” that these students will end up at the top of the class (and, in fact, is a bit odd to award them cash for future law school performance). If this were truly the motivation, then schools should really award scholarships after the first year to high-performing students (who, it should be noted, would be, at that time, the least in need of scholarship aid, as they would have the best employment prospects).

But it does allow schools to quietly expand their scholarship budget, at the expense of current students. Suppose a school has a $5 million annual scholarship budget. That should work out to $15 million a year (three years of students at a school at any one time). But if 20% of scholarships are eliminated, that budget can drop to $13 million.

I find it difficult to justify conditional scholarships (and it is likely a reason why the ABA began tracking and publicly disclosing the data for law students). I think the principal reason for them is to attract students for admissions purposes, not to anticipate that they will perform. And while other student debt metrics have been eliminated from the methodology because they are not publicly available, this metric has some proxy to debt and has some value for prospective students. Including the metric could also dissuade the practice at law schools and provide more stable pricing expectations for students.